The Last Supper: fresco or not?

Last Supper: is it a fresco or not?

Among all religious subjects, the Last Supper has been a favorite source of inspiration for many works of art, and numerous are the great masters who addressed this theme in some of their best-known masterpieces. As far back as the centuries of early Christianity, pictorial representations of the last meal of Jesus were central to Christian faith and worship. Some have been found in the Roman catacombs and have been among the most represented in sacred art since the earliest of times.

Later representations of it can be found in Monza, in the sublime Saint Apollinare in Ravenna and even in a Syrian Codex kept in the Laurentian Library of Florence. In more recent years, the Last Supper of Gebhardt has been regarded as a true masterpiece.

Fresco Arte reproduction of the Last Supper, for sale.

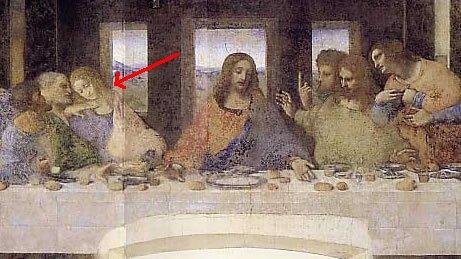

Of course, the best known of all remains the Last Supper by Leonardo da Vinci, even though other outstanding masterpieces were executed by Tintoretto, Veronese and Ghirlandaio (Michelangelo’s master).

However, Da Vinci's Last Supper has become one of the most widely appreciated masterpieces in the world. It began to acquire its unique reputation immediately after it was finished in 1498, and its prestige has continued to grow. Despite the many changes in taste and artistic styles throughout the centuries – as well as the unfortunate deterioration of the painting itself – its status as an extraordinary creation has never been questioned nor doubted.

The outstanding features of the Last Supper not only the highly artistic merits of the painting, but also Leonardo's expressive mastery. Leonardo's Last Supper is an ideal pictorial representation of the most important event in the Christian doctrine of Salvation: the institution of the Eucharist. There are countless copies and representations of the Last Supper in homes, places of worship and museums throughout the world. However, when thoughts turn to the Last Supper, it seems that only Leonardo's representation comes to mind.

This amazing work by Leonardo has also been subject to much attention due to the number of restorations it has had to face since its completion, in the 15th century. The most recent restoration lasted twenty years and has been the subject of much controversy. One of the most frequent pungent criticisms leveled at this influential painting is that it has been "repainted" rather than "restored".

However, restoration has continued to be an ongoing necessity for this masterpiece due to the unprecedented manner in which Leonardo painted it. Although restoration may have altered Leonardo's painting to a degree, it has also prolonged its life, a duty, to certain extent, we owed to future generations.

There is something else, just as intriguing to art buffs, related to the Last Supper. Most people assume that, as it was painted on a large wall, Leonardo used a fresco technique, but is it truly so?

In fact, no.

Leonardo chose to paint his Last Supper using a "pittura a secco," which means he applied colors on a dry surface, using a binder such as animal glue to make the color stick. Basically, he applied to a wall the same type of technique he would have used to paint on canvas or wood. Fresco was a well established technique by the time Leonardo was commissioned the Last Supper by Ludovico il Moro (1495), but he was not too fond of it: frescoing a wall implies being quick and having very limited possibilities to correct or modify what is already painted, factors the volatile and moody genius of Leonardo badly adapted to. Using "pittura a secco" for the large wall of Santa Maria delle Grazie chosen for the work seemed, at the beginning, a far better choice: Leonardo would have had time to correct and adapt what he had already painted, as well as giving to his work different nuances and darker colors, which he preferred.

Unfotunately, Leonardo grossly misjudged the consequences of his choice, failing to understand this technique was not good for the type of location he worked in. The colors, initially vivid and strong, began to show signs of fading as soon as the mid-16th century, when Vasari himself noted how parts of the painting had been literally disappearing from the wall.

In truth, most of the restoration works on the Last Supper carried out in the past century have been aiming exclusively at reverting, or at least reducing, a type of damage which would have not happened (or at least not to that extent) should Leonardo have chosen to fresco rather than dry paint his masterpiece.

So, no. Leonardo's Last Supper is not a fresco, even though many of us still associate this iconic image to such technique.