Cimabue

The hidden master: Cimabue

Destiny seems to have relegated the Florentine master Cimabue to a world of shadows, if compared to other major art masters.

His fame, in part, was obfuscated by the popularity of other artists, particularly Giotto. It is also true that many of his works have been either lost over the centuries, or severely damaged by natural disasters.

Even the date of Cimabue's birth is known only approximately, placed between 1240 and 1245. The first historic fact of his life is a notation that on 18 June 1272, he was present in Rome as a witness to the assumption of patronage by Pope Gregory X of the monastery of Saint Damiano. The fact that he was called to witness the event suggests that at the time Cimabue was already a well-known and respected figure. It is also significant that Cimabue had traveled to Rome, and was thus exposed to the influences of the classical school.

Following that, historical information is available only for an event some 25 years later, when between 1301 and 1302, Cimabue was called to Pisa to complete the mosaics in the cathedral. Also in 1301 the hospital of Santa Chiara charges the master with the painting of a large alter piece, which has unfortunately been lost. The year 1302 also marks the death of Cimabue.

Not many, unless well versed in history of art, are familiar with the work of Cenni di Pepo, commonly known as Cimabue. His works, of extraordinary beauty, were somehow shadowed by those of his most famous apprentice, Giotto, but his importance in the history of Italian art and, in particular, for the evolution of frescoing techniques, should be kept in mind. Even Dante, in his Purgatory, dedicated a series of tercets to him, outlining how the fame of his pupil cast a seemingly never-ending shadow on his own.

If not as famous as his student, Cimabue has been just as essential to the development of western art; in fact, we could say Giotto would not have been able to create the same type of masterpieces without the presence of Cimabue. Up to then, painters were still greatly influenced by Byzantine art: this was characterized by a large use of gold pigments and by the stern hieraticity, the motionless impassibility of body and expression, of its figures (think of the beautiful San Vitale Basilica in Ravenna).

Cimabue, who did have Greek and Byzantine masters, managed to transcend their artistic representation and began to play with volumes, which he enhanced with an intelligent use of color. His figures lost the immobility typical of Greek and Byzantine art, and gained vitality, especially through their posture, but also through the draping of their clothing and its color. Most of all, Cimabue’s figures were no longer emotionless: for the first time since the end of Roman art’s dominance in the western world, frescoes returned to be mirror of the whole spectrum of human emotions and feelings.

Despite the paucity of information, subsequent research has led to the conclusion that Cimabue was perhaps the first innovator in Italian art who overcame the stylistic rigidity of Byzantine art and moved to more varied use of colors and to more natural representations of images. The art historian Vasari was the first to attribute the fresco decorations in the Basilica of Saint Francis at Assisi to Cimabue, with the exception of those regarding the life of Saint Francis which were painted by Giotto. However, while Cimabue is recognized as an innovator in art history, it was Giotto who carried forward the innovation and promoted a major change in the art form.

Among the major works attributed to Cimabue is the large cross in the church of Saint Domenico in Arezzo. It is believed that the painting dates to around 1270. An innovative element is that is depicts Christ in the dramatic moment of his death, underlining the commonality with human suffering. This painting, while innovative in many respects, is not yet the full expression of Cimabue's later style.

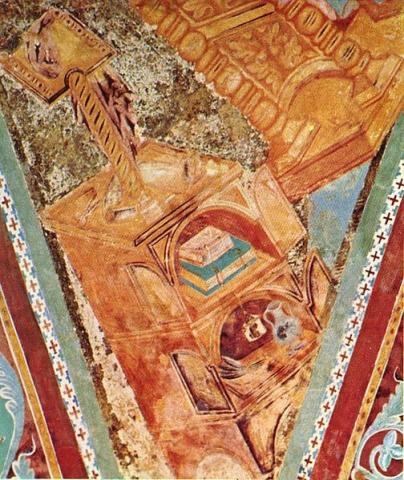

Famous is his work in the Saint Francis' Basilicas in Assisi. Seven of his best known frescoes are in the Vault of the Evangelists, in the Basilica Superiore (Upper Basilica). The other frescoes in Saint Francis' Basilicas are grouped in three distinct cycles: the Storie della Vergine (life of the Virgin) cycle is formed by eight frescoes; seven are those from the Scene Apocalittiche (apocalyptic scenes) cycle, and finally five are within the Storie Apostoliche (stories of the apostles) cycle. The decorations are completed by two large frescoes of the crucifixion, both on the side walls of the church.

Unfortunately, many of Cimabue's frescoes have reached us in a compromised state. Cimabue made extensive use of tempera touch-ups on dry plaster to complete his works, and over the centuries many of these deteriorated to the point of crumbling off the walls. Moreover, the white color used to highlight portions of the paintings has become severely oxidized, causing an inversion between light and dark hues in the pieces. The earthquake of 1997 had severe adverse effects on the frescoes due to the collapse or cracking of supporting walls, but intensive restoration efforts have helped to solve, at least in part, these problems.