History of Fresco Painting I

HISTORY OF FRESCO PAINTING

From prehistory to current days, artistic development has been reflecting the societies in which it occured and their geographic locations.

The evolution of mural painting techniques also mirrors specific moments in history and its influence on artistic production and styles. Fresco is an ancient form of painting, which evolved throughout the centuries. The Greek and the Romans are known for their penchant for this type of technique, but man began using rudimental forms of wall painting much earlier.

Prehistoric and early fresco painting

The first paintings on walls were found in a cave in Chauvet, in France, and date back to no less than 30,000 years ago.

Some 15,000 years ago, frescoes were created in other caves in Lascaux, France, and Altamira, Spain. These early examples of fresco painting are testimony of the long and varied history of this art form. The early frescoes, painted on the dry limestone walls of the caves, contained remarkably expressive and realistic figures of horses, bison, bears, lions, mammoths and rhinoceros, which continue to fascinate researchers and art historians.

Because painted on a dry surface, we would call them today affreschi a secco, or “dry frescoes” if you translate literally. The technique, in fact, had been used in some Medieval and Renaissance works, including Leonardo’s Last Supper.

By 1500 BC, mural art techniques evolved, and artists began to paint on fresh plaster, which allowed for much more flexibility, as locations for paintings could be chosen on discretion.

The earliest known examples of such frescoes are found on the island of Crete, in Greece, in the royal Palace of Knossos. The most famous among them is called the Bull-Leaping, and depicts a sacred ceremony in which individuals jump over the backs of large bulls. This piece was painted on a series of plaster panels, which had been previously stucco relieved, which brought art historians to catalogue the frescoes, in fact, as plastic art.

Some similar frescoes have been found in other locations around the Mediterranean basin, particularly in Morocco, but their origin is subject to speculation: some art historians believe that wall painting artists from Crete may have been sent to Morocco as part of a trade exchange, a possibility which emphasizes the importance this art form may have had at the time.

In later centuries, frescoes made their appearance in ancient Greece, but unfortunately only few of these works have survived. Some of them are, in fact, in Italy at Paestum, in the Salerno province of Campania, which was once part of Magna Graecia. They have been found in a tomb, called Tomb of the Diver, whose name is linked to the image represented in one of frescoes themselves: it pictures just what it says, a male figure forever immortalized while diving into the waters of the Mediterranean. Simple in its iconography, this piece of ancient painting, just as the other, larger one, which depicts a banquet and runs on two of the tomb’s walls, helped historians to get one more glimpse into the life and society of Ancient Greece. This, too, is the beauty of art.

Pompeii

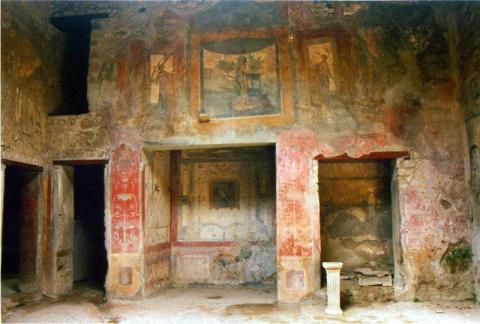

Above: Wall Fresco in Pompeii

Speaking of Roman frescoes means speaking of Pompeian wall art.

Layers and layers of ashes and volcanic soil protected the cities of Pompeii, Herculaneum and Stabia from the ravaging of time and gave back to the world, seventeen centuries after that fatal day of October, some of the best preserved vestiges of the greatness and beauty of the Roman Empire.

Buildings, roads, fountains, homes and stores, all was kept dormant for centuries by a heavy blanket of dark soil: thanks to this, the state of preservation of Pompeian frescoes is unrivaled.

It is inevitable to think of the absolute irony of the fact that a terrifying act of destruction, such as a volcanic eruption, may have been, at once, also the reason for the preservation of Pompeii, its frescoes, its life. Lava stones, soil and ashes did not only protect the city from the weather and the inexorable passing of time, but also from centuries of wars, fighting and potential neglect.

Pompeii’s tragedy became a mirror into its marvels and beauty and those of the Empire of which it was part. Marvels and beauty we can still admire today.

The prosperity of Pompeii as an agricultural and trading center gave impetus and support to many artistic forms. Fresco artists were particularly sought after, because Roman homes were richly decorated and wall painting was an essential part of a home’s “furniture”. The Romans did not like objects around the house too much; in fact, if we saw one of their houses when still lived-in, we probably would have found them strangely empty. Decoration, warmth and even coziness were all given by wall paintings, hence the absolute importance of mural art.

But frescoes were also status symbols: the years immediately preceding AD 79, the date of the Vesuvius eruption, Pompeii was rich and its people enjoyed luxury, wealth and beauty, all showcased on the walls of the powerful and rich of the city. Wall decor paintings were so essential that modern archaeologists have managed to recognize several different hands at work only in the city of Pompeii, which means plenty of artists were called to the city to paint.

Mirrors of beauty and wealth, status symbols, but also, just as it happened for the Greek frescoes of Paestum, a modern peephole for us to witness and learn about the life of those times.

For instance, Pompeii has preserved a fresco illustrating events narrated by Tacitus in his Annales: a sport event between Pompeii and a rival town, Nuceria Alfaterna (today’s Nuceria) which quickly escalated into a full blown fight, complete with daggers and swords.

The fresco depicted the events with a powerful attention to details: even a vendor, looking worried for the possible negative effects of the fighting on his trade, was vividly sketched in the piece. The painting was found on the wall of a plebeian house in Pompeii, and is today kept in the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli.

As we said, the austere style chosen for home building in Pompeii and the Roman penchant for sparse furnishing, encouraged the use of fresco painting for decorative purposes. The walls were painted in monochrome colors of red, yellow and black and were embellished by paintings of figures, landscapes, masks and garlands.

Color application techniques were so refined and perfected that they allowed the frescoes to survive for thousands of years. It is noteworthy that even to this day, researchers have not been able to fully discover the secrets of Pompeian artists’ painting techniques, nor those that permitted to their works to last for so long.

The houses of Pompeii, even those of the wealthiest owners, were surprisingly limited in size. However, the smallness of the rooms was disguised by the broadened horizons deriving from the ubiquitous presence of beautiful wall paintings depicting harmonious landscapes, country scenes, magnificent views of the sea and limpid blue skies, splendid, fruit laden trees. An ante-litteram system of “trompe l’oeil”, used to create the illusion of space where there wasn’t any, and beautiful views of nature where only a wall could be seen before.

Particularly outstanding examples of the decorative heights reached by the fresco artists of Pompeii are to be found in the Villa of the Mysteries: the main fresco, which occupies all remnant walls of the villa, represents a myriad of enigmatic figures engaged in a ritual celebration of the Sacred Mysteries. These frescoes are among the best preserved and most visited works of art in Pompeii.

The inhabitants of Pompeii were quite superstitious, as proven by the many amulets and objects against bad luck found in the city. These ranged from simple amulets to carry around or wear, to small bronze hands forged in a gesture to ward off the evil eye and to attract the gods’ good grace. Because Pompeians, and Romans in general, knew the propitiatory power of symbolism and representations associated to well being and prosperity, vestiges of it are found a bit everywhere in Pompeii: one symbol stands above all, the phallus. Paintings or sculptures of male genitals are found a bit everywhere in the city, but you should refrain from interpret their presence from a sexual point of view.

Phallic images were considered the most effective of all amulets and for this reason they were often placed on the main door of stores and houses, sometimes even drawn on the ground. Phallic symbols were gradually extended to fresco paintings, where they became an emblem of health and wellbeing: in other words, there was nothing erotic in the presence of penises on the walls and streets of Pompeii!

Above: our reproduction of a pompeian fresco

Of course, we all know sex was important to the Romans and the people of Pompeii were no exception. One of the most visited sites in the town are the ruins of the lupanare, Pompeii’s largest brothel, a place frequented, when activity was in full swing, by hundreds of men. In truth, men did not even need to visit a brothel for sex, because it was customary for waitresses in public drinking places, as well as slaves, to perform under payment of a fee. Sex in Pompeii was not only prostitution, though (let us not forget, however, that prostitution was an entirely normal activity in Roman times): Romans lived their sexuality with naturalness and ease and never considered it a taboo.

It is also for this reason that sexual relations were portrayed in frescoes explicitly in all of their variations and combinations, and the inhabitants lived side by side with these images as though they were still life or landscape paintings. The erotic frescoes of Pompeii certainly underline the immense gap existing between Roman culture and current day more. If you decide to visit, be aware you must be an adult, as these frescoes are not generally open to the wider public.

Another significant aspect of Pompeii’s frescoes is the mundane manner in which they treated religious and spiritual matters. This was, indeed, a trend of the times. In their various representations, the divinities are humanized and, above all, they are used as a theme to decorate the home of wealthy Pompeians.

Decorative religious frescoes of this sort include The Wedding of Mars and Venus, The Marriage of Jupiter, Narcissus at the Fountain and other subjects of historical or mythological nature. However, the divinities closest to the hearts of the inhabitants of Pompeii were those linked to agriculture, health and good fortune. These were those most represented in the city’s frescoes.

These frescoes were, to many, a true means to show social status and wealth; for this reason, their richness, intricacy and feast of movement and colors could match what we would today call Baroque aesthetics. Such need to flaunt wealth, also through artistic expression, is often attributed to the underlying insecurity of a consumer-focused society and in particular to a strong sense of financial instability, associated to a continuous fear of poverty. In this, Pompeii was extremely modern, the behavior and fears of its citizens specular to those of people in other centuries and countries.

Other major early period fresco paintings

A different spirit permeates the religious wall art painted by early Christians living in Rome during the late second and third centuries AD. The early Christians frescoed the walls and vaults of their underground tombs, or catacombs, with Christian symbols and scenes from the Bible.

The sacred nature of fresco painting was also prevalent in Asian and Eastern European civilizations. Archaeologists have found frescoes in China, at Liao-yang (100 BC) and Tun-Huang (AD 500-800), as well as Ajanta, India (AD 500-700), the latter depicting scenes from the life of Buddha and stories of his early incarnations. Frescoes of Byzantine origins, painted between the years 500 and 1300, were found in modern Russia, Ukraine and in France.